YWR: S&P $10,000

I’m going to propose something radical.

That we’re going much higher in the S&P 500 and NASDAQ.

It’s a bit of a change of view for me, but now I wonder if we are going to $10,000 on the S&P 500 by 2027. Yes, international markets still go up, but so does the US.

My base case coming into 2025 was that we were too pumped up on American Exceptionalism, cash levels were too low, and the NASDAQ would fall 20%, or below $16,000.

Well, that happened, but surprisingly, the NASDAQ has completely recovered.

My game plan was also that US equities might be dead money for 1-2 years while the rest of the world outperformed.

I also thought 10 year bond yields would go to 6% based on continued US economic growth, and inflation.

But a new possibility has arisen.

That we are about to get a repeat of 1999 again.

And the S&P is going to $10,000 or a P/E of over 30x

I’ll explain how I get there, but first we have to set the table.

We have to review a few interesting concepts from behavioural economics.

#1. The Blue Eyed Islanders

I love the Blue Eyed Islander Puzzle.

It’s a puzzle about logic, math and common knowledge.

I’m less interested in the math of the solution, how many days it takes the islanders to figure out if they have blue eyes.

What interests me is the concept that ‘common knowledge’ within a group can suddenly change.

Markets do this too.

In the Blue Eyed Islander problem on the 100th day all the Blue Eyed Islanders realise they have blue eyes and kill themselves.

It’s nothing, nothing, nothing for 100 days, then suddenly group realisation and mass suicide.

Sudden changes in common knowledge

Put a pin in that.

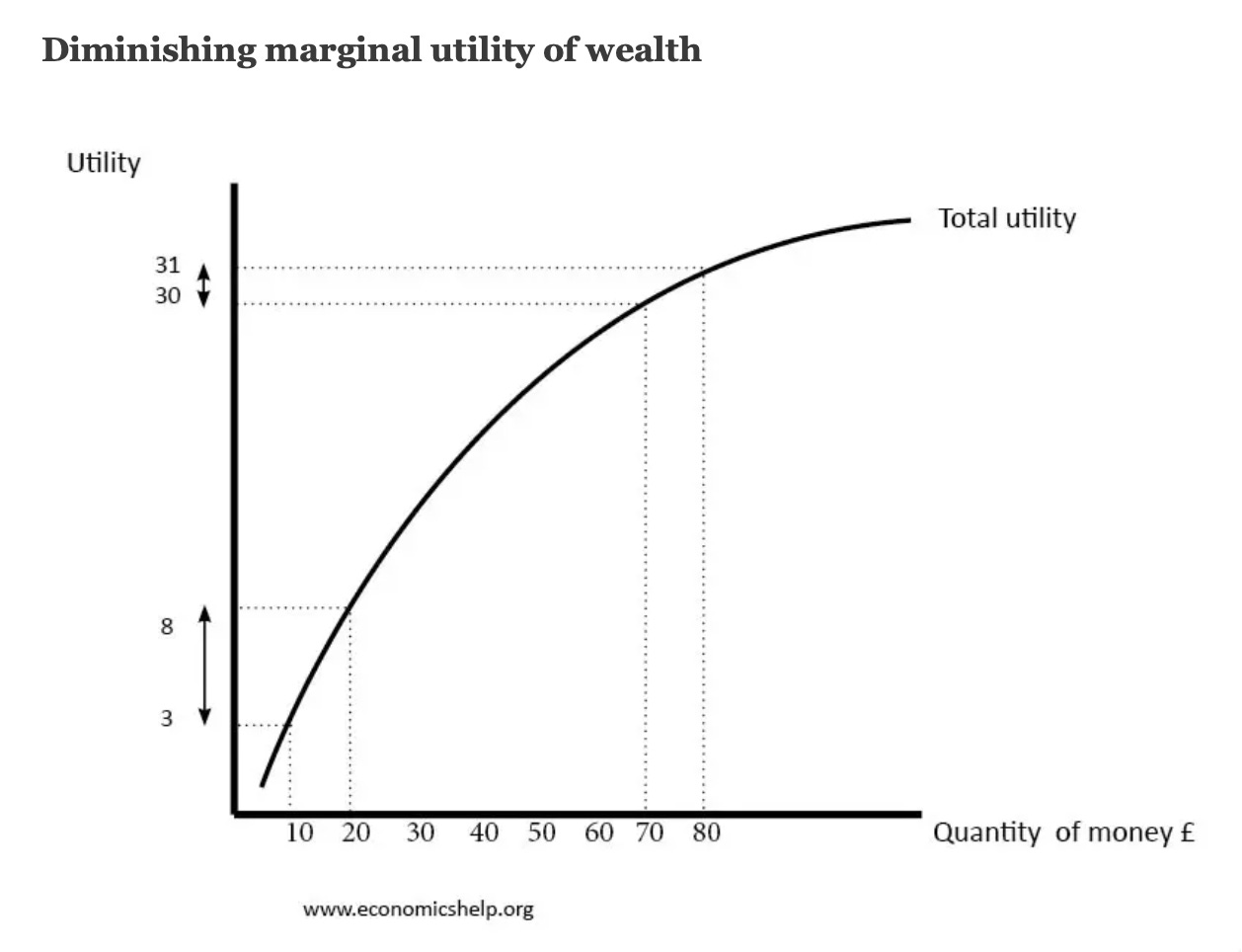

#2 Diminishing Marginal Utility of Wealth

This concept is the basis for so much human behaviour. You will see it in everything.

The idea is that in general you are less happy to lose $10,000 versus gaining $10,000.

For example, if you only had $20,000 and I offered you a 50/50 bet to gain or lose $10,000 you most likely wouldn’t take it. Yes, some gamblers would, but most won’t.

You realise it would be nice to have $30,000, instead of $20,000, but the bear case of dropping to $10,000 would be catastrophic. Economists run tests on this, offering sample bets to real people, and in most cases people need close to a 2:1 payout to that bet (for example +$20,000 or -$10,000). It depends on the person, and the starting point (how much money they have), but in general there is an asymmetry. The 2nd derivative of the curve is negative. If you have money you prefer to keep it.

This asymmetry shows up in lots of interesting things.

It’s why everyone wants a job instead of starting a business. It’s why pension funds haggle over 25bps of management fee and then give away 20% of performance fees (explicit costs versus opportunity costs).

It’s why wealthy families are conservative with their asset allocation when you could argue they are in a great position to take risk.

Put another way, fear of loss means people are willing to leave a lot of upside on the table.

It explains the seemingly illogical human behaviour that you can offer someone a bet with a statistically positive outcome and they won’t take it.

Leaving upside on the table.

Put a pin in that.

Two more then we’ll get to the S&P 500.

#3 Rules of Thumb (Heuristics)

In complex situations people love ‘rules of thumb’. The technical term for this is Heuristics.

The human reality is that everyone is not Einstein. We are always looking for mental shortcuts, especially around complicated probabilities and payoff scenarios.

For example, if I ask you how many cards in the picture below you will probably guess between 30 and 52. You might not get it correct, but you will be close.

But what if I asked the surface area of all the cards?

Now you have no idea. You have to stop and think. The math is hard. The range of guesses and errors is much higher.

People struggle with complex calculations and look for simple rules of thumb.

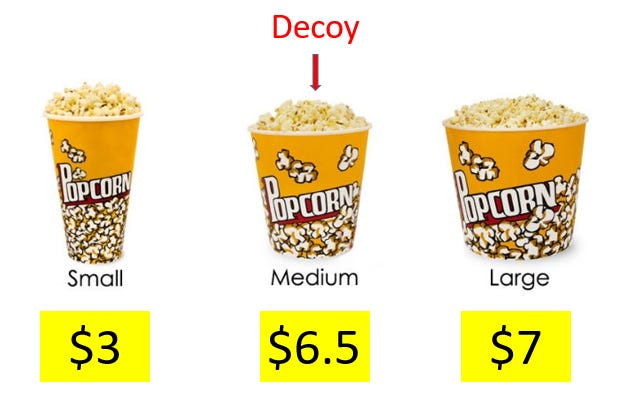

#4 Choice Architecture

Advertisers know whether you think something is a ‘good deal’ depends on your choices. This is the science of nudging you through choice architecture.

For example, at first the $7 popcorn seems expensive.

But what if we add a ‘decoy choice’?

If we add a medium for $6.50 then suddenly $7 seems like a ‘deal’.

“Sir, for just 50cts more you can get a large popcorn.”

Our perception of value depends on the choices available.

Put a pin in that.

So how do Blue Eyed Islanders, $7 popcorn, Rules of Thumb and the Marginal utility of Income lead to $10,000 on the S&P 500?

Let’s put it all together.

Starting with why the S&P is massively undervalued.